Our Earliest Days

The Origins of Freemasonry in England

Condensing almost 300 years of history in one web page is impossible, but here is a brief (and necessarily incomplete) overview of the first few decades of our adventure, in the wider context of the early days of Freemasonry in England.

Although Freemasonry is the largest and one of the oldest fraternal organisations in the world, with lodges in almost every democratic country, its precise origins are somewhat lost to time. What we do know is that the story starts with British medieval stonemasons, of which we have records and documents dating from the 14th century.

A lodge, or loge, was originally just a site hut for the men building a castle, cathedral, or other large stone edifice. Here, the stonemasons would eat, rest and store their tools, and it was in this building that their art was communicated to suitable apprentices, who would then be tested on their proficiency, so that they could progress through levels of increasing skill, culminating in the experienced craftsmen whose splendid work has survived for centuries.

The term “lodge” gradually shifted in meaning, and started referring to the group of stonemasons who met in that place. In time, and in order to protect workers’ earnings against fluctuations in supply and demand, lodges began to behave more and more like guilds, regulating the stonemasons’ trade and establishing rules on appropriate wages, the required period of apprenticeship, the handling of contracts, fines for transgressors, and even the necessary safety measures to be employed on building sites. They also functioned as an early form of welfare system, offering support to members in distress and, if they passed away, to their widows.

As decades passed, some lodges started admitting members of the gentry and local dignitaries into their ranks, increasing prestige and authority, and with the very tangible advantage of enabling members to network with those who set regulations and commissioned the most lucrative jobs. The impact was profound, with these lodges transforming from operative organisations into social and convivial clubs, where the stonemasons’ arts became less and less relevant.

It was the birth of non-operative lodges, which flourished through the 16th century until things rapidly changed in the mid-17th, when a surge in urbanisation created a great demand for stonemasons, who had to be brought in the cities from the provinces. The requirement for workers was particularly acute in London after the Great Fire of 1666. In this environment, authorities had no choice but to relax the regulations, with the result that masons could easily find employment without having completed a formal apprenticeship or being members of a lodge, and thus without paying the corresponding dues. Lodges rapidly lost their control over the trade, and the last link with their operative heritage was severed.

From Non-Operative to Speculative

As these non-operative lodges did not yet have a distinctively philosophical (“speculative”) character, they were still quite different from modern ones, and here is where things become particularly mysterious: in Scotland we have abundant records showing a gradual transition from operative all the way to speculative, but in England things are far from clear and the debate is still ongoing.

Most masonic historians in the early and mid-20th century (e.g.: Knoop, Jones, Carr) thought that English lodges went through a gradual transformation as their Scottish counterparts, but more recent researchers (e.g.: Hamill, Berman) believe that there is simply not enough evidence of such a direct lineage: in their opinion, English speculative lodges did arise independently, in the wider context of the Enlightenment period, as private societies for philosophical discussion, moral improvement, mutual support, and even simple entertainment, borrowing symbols and metaphors from the building trade. Research is still very active, and as more and more material is being analysed a number of hypotheses are being evaluated.

In these speculative lodges, the tools and techniques of masonry became metaphors for moral instruction, and the building of a fine structure evolved into a symbol for building a better life. The principles of brotherly love and mutual support acquired a broader, more universal meaning, and lodges gradually opened their doors not only to men of all professions, but in the spirit of Enlightenment of all races, nationalities and creeds.

Coffee shops and especially taverns were ideal settings for these circles. In the words of Christopher Gotch: “Taverns were rarely large; hence their proliferation. At best they were clean and cosy, at worst squalid and uncomfortable; but all were venues for the exchange of gossip, scandal, confidences, contracts, money and even trysts for sex. Business folks, masons included, invariably spent as much time at the tavern as they did at home or in the office, such was the hubbub and multitude there and, more often than not, a handshake over a pot of porter clinched a business deal. […] The main delights of masonic refreshments were pipe-smoking – long clay churchwarden pipes were provided free by the landlord – and quaffing punch, from a large bowl common to all, or wine or port, with much song-singing; all carried out during lodge proceedings.” It is no surprise that our ancient Minutes are often difficult to read: no secretary wished to miss the toasts or the merriment. A rather different atmosphere from modern Masonic meetings!

When in February 1733 our Lodge was officially constituted at the Crown and Mitre Tavern in Labour-in-Vain Hill, our meetings would have looked very much like those just described.

What’s in a Name?

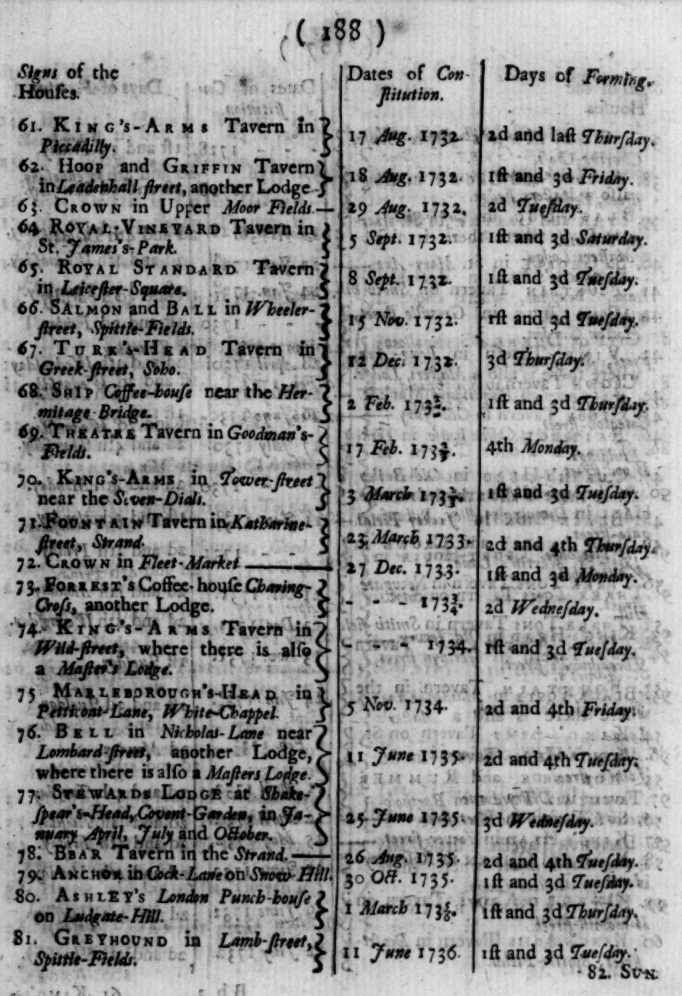

Early lodges were self-governing bodies without a central authority, but as Freemasonry grew in popularity there was a need for a more structured approach, and in 1717, four London lodges met at the Goose and Gridiron Ale-House near St Paul’s to found the Grand Lodge of English Freemasons. If you happen to be in the area, look out for a blue plaque commemorating the event — it was placed there on the initiative of Bernard Williamson, a member of our Lodge!

Founding a Grand Lodge proved to be a brilliant idea: the organisation grew rapidly, with other lodges in England happily joining the club, which quickly evolved from a sort of gregarious society into a true governing body. When we were constituted in 1733, we were the 110th English lodge to do so. We were not yet known as “Strong Man Lodge”, however: in the early days of Freemasonry, lodges were identified by the name of their meeting place, which might be an inn, a tavern, a coffee house, or even a private home. At our inception, we were simply known as “the Lodge at the Crown and Mitre, on Labour-in-Vain Hill”, which was a short street near St Paul’s. We moved venue several times in the following years, and acquired our current name only in 1764, when we started meeting at the Strong Man Tavern in East Smithfield.

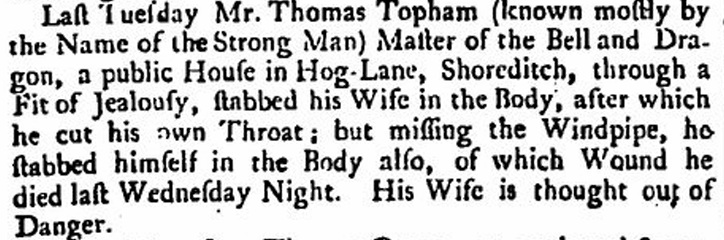

The tavern was named after its former landlord, Thomas Topham, a well-known Londoner famed for his extraordinary feats of strength. While there is no evidence that he was a Freemason, we do know that he kept company with Dr John Theophilus Desaguliers, Fellow of the Royal Society, experimental assistant to Sir Isaac Newton, and the third Grand Master of the Premier Grand Lodge of England.

Much is known of Thomas Topham’s life. The son of a carpenter, Dr Desaguilers himself in his “An Account of Things Performed by Real, and by Pretended Strong Men” informs us that he was born circa 1702. At just 24 years of age, he became host of the Red Lion near the old hospital of St Luke. The area, Moorfields, was known as the “gymnasium of our capital”, a gathering place for cudgellers, wrestlers, backsword players and boxers from all parts of the metropolis.

In October 1733, Thomas demonstrated his strength at a meeting of the Royal Society. These feats were recorded in the Society’s library and in Dr Desaguliers’ book A Course in Experimental Physics.

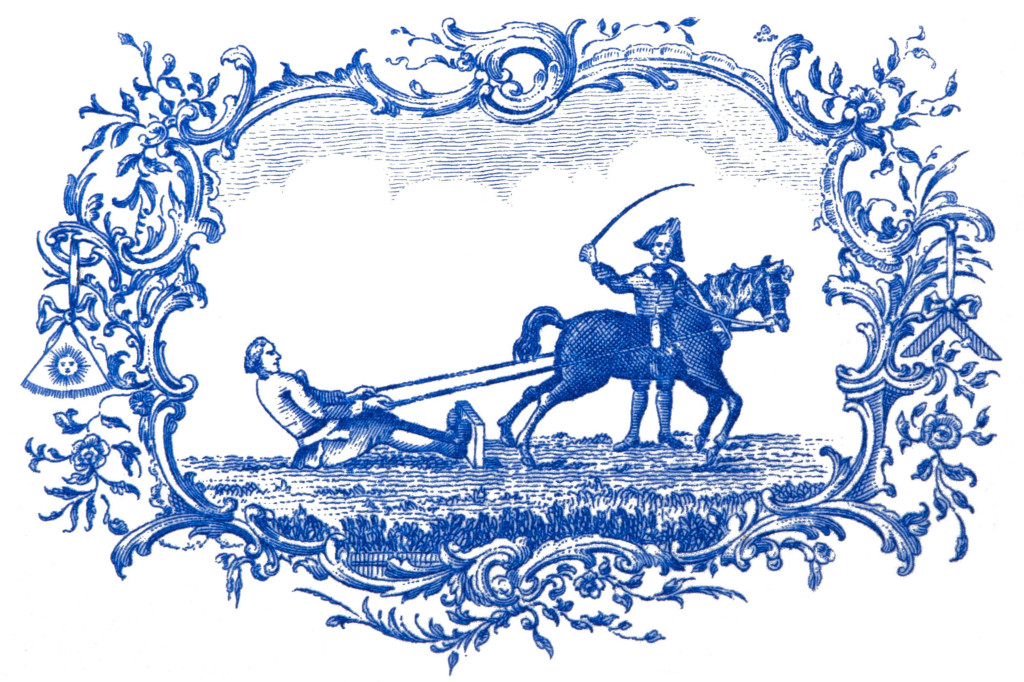

One of his earliest public demonstrations involved pulling against a horse while lying on his back, his feet braced against the dwarf wall that divided upper from lower Moorfields. This remarkable image has long been used as the emblem of our Lodge.

Dr Desaguliers described many of Thomas’ feats in painstaking detail, and believed that, in the proper position, he could have pulled against four horses.

Thomas Topham’s fame grew, and he toured widely across England, Scotland, and Ireland to demonstrate his strength. Even Harry Houdini wrote of him in Miracle Mongers and Their Methods.

Unfortunately, Thomas’s life came to a premature end in 1749, when one fateful day he returned home to find his wife with another man. In a fit of rage, he stabbed her and then retired to his bedroom where, overcome with remorse, he stabbed himself multiple times. He died the following day, but his wife recovered from her wounds and continued to run the business, which later became known as the Strong Man Tavern.

And so ended the life of a very unusual man. Our Lodge moved to the Strong Man Tavern in 1764 and remained there until 1813, at which point our name, the Strong Man Lodge, became permanent. It must have been a pleasant and welcoming venue, as it marked our third-longest stay, after Freemasons’ Hall (where we have been meeting since 1955) and the Holborn Restaurant, which we used from 1898 until 1954.

Interestingly, a few articles in Masonic periodicals during the 19th century claimed that Thomas Topham was a member of our Lodge. However, there is no evidence to support this: the connection between the man and the Lodge is only indirect, and dates from after his death.

One Strong Man, Many Sea Captains

The reasons for moving from one place to another varied considerably: sometimes, a growing membership forced us to seek more spacious venues. The quality of food could be an equally valid reason, not to mention the price of beverages: we know that on one occasion the Lodge voted to relocate after the landlord raised the price of a barrel of brandy by two shillings and sixpence, a half crown.

As far as we can tell from the records, we were never evicted for annoying or riotous behaviour, although there are occasional references to complaints from neighbouring citizens about the excessive noise of Brethren departing late into the night. In our defence, this was by no means an uncommon occurrence among London lodges of the time.

As mentioned earlier, our very first meeting place was the Crown and Mitre tavern in Labour-in-Vain Hill, which was the southern portion of Old Fish Street Hill, a stone’s throw from St Paul’s Cathedral. The sign issued by the brewer, William Baggott, showed two women trying to scrub a black man white, implying a labour in vain. With it, the brewer was challenging the competition to produce ale as good as his, which suggests that the earliest members of our Lodge might have chosen the venue for the quality of the drinks. Oddly enough, the same house was also known by another name: the Rummer and Mitre (a rummer being a large drinking glass shaped like a sundae glass).

We stayed only briefly at the Crown and Mitre, and in the same year moved to the Ship Coffee House, near Hermitage Bridge, between Tower Hill and Wapping. It was not the most reputable part of London: not only it was popular with seamen and dockers, but also with criminals and prostitutes. Sanitation was non-existent.

The area might not have been the most elegant, but it had one clear advantage: plenty of sea captains and officers willing to join Freemasonry, and our Lodge made the most of it. We know that many of them were among our members during that period, and that our Lodge was certainly chosen by the Merchant Fleet as a favoured venue for membership as early as the mid-1740s. It is, however, difficult to determine precise numbers, as not all Secretaries recorded captains and officers with their proper titles. Unsurprisingly, turnover was high, with many members only able to attend one or two meetings before setting sail again.

Instead of meeting at a tavern, we chose a coffee house, a far more respectable establishment. Coffee houses were becoming important meeting places, and records show a thriving community in the area, with tallow chandlers, victuallers, bakers, bricklayers, and wig makers. In the City of London, coffee houses played a significant role in the development of insurance, stockbroking, and commodity trading.

We still have records from those early years, as our Secretaries at the time appeared to take great care in keeping track of meetings and membership. Unfortunately, our very first book of Minutes, covering the meetings from 1733 to 1760, was lost in a fire. However, we have a Quarterage (subscription) Book dating from January 1749, listing the names of each member and the amount paid per quarter, typically 6/6d (6 shillings and 6 pence). Elections were usually held in December and June, so changes often occurred every six months, rather than annually as is the case today.

Initially, Secretaries did not bother recording members’ professions or places of residence. The first known exception was on 18th June 1752, when a Bro Whiteway, described as a “Gentleman of Walthamstow in Essex”, was initiated.

The number 45 is somewhat misleading, as lodge numbers changed several times during the 18th and 19th centuries. These were reallocated by Grand Lodge as other lodges closed or merged. We were originally No. 110 in 1733, became No. 98 in 1740, No. 68 in 1755, and so on, until finally settling on No. 45 in 1863. However, according to John Lane’s Masonic Records we are the 19th or 20th oldest Lodge in England (Royal Cumberland No. 41 has a later Warrant but earlier records. You choose).

Those Old, Old Chairs…

The Lodge possesses a number of valuable artefacts, our Tracing Boards, for instance, are truly remarkable, but none are so prized as the set of three magnificent mid-1700s chairs used by the Worshipful Master and Wardens during our annual Installation night. When not in use, these chairs can be seen at the Museum at Freemasons’ Hall. They are Chippendale-style, and while the date of manifacture is uncertain, a reasonable estimate places them in the 1750s. What we do know is that they were by no means inexpensive. Fortunately, the Lodge enjoyed a steady income at the time, largely thanks to the constant influx of sea captains being initiated, and this most likely funded their purchase, although a generous contribution from some of the more affluent members cannot be ruled out.

The chairs have been fully refurbished since then, and it is always a great pleasure, and one of our most cherished traditions, to bring them out once a year. It is also quite a surprise for the newly installed Worshipful Master, unless he happens to be particularly tall, to discover that his feet cannot reach the floor!

At the time, we were meeting at the Samson and Lion in Butchers Row, East Smithfield. The Ship was by then operating as an inn and was probably too crowded for our liking. Meetings were held twice a month, on the 1st and 3rd Thursdays, and included both ceremonies and rehearsal sessions.

Our first recorded Third Degree ceremony took place on 17th January 1760, although we can be confident that the Lodge conferred that Degree prior to that date, it is simply that no earlier Minutes have survived. However, we must remember that in operative Masonry there were originally only two Degrees: Entered Apprentice and Fellow Craft, with a Master Mason being simply a Fellow Craft who employed other Masons. Early speculative Masonry followed the same structure, and the trigradal system we now practise only emerged in the 1720s. This new system was likely adopted relatively quickly across English lodges and had become standard by the time the rival Grand Lodge (the “Antients”) was founded in 1751.

On 18th August 1763, we see the first recorded instance of a clergyman, a certain Rev. Entick, becoming a member of our Lodge. Exactly five years later, on 18th August 1768, an Initiate failed to appear for his Ceremony and consequently forfeited his deposit. A few months after that, on 19th January 1769, we find the earliest known case of a Candidate not being accepted: Mr Simpson was “blackballed”.

The 1770s mark the first decade for which we have a complete set of Minutes, and it is striking how closely the Lodge’s workings already resembled our current practice: aprons, Past Master’s jewels, a banner, summonses, certificates, Tylers, and even an Organist are all mentioned. Although the ritual was still quite different (its modern form took shape after the union of the two Grand Lodges in 1813), current members would undoubtedly feel quite at home at Strong Man Lodge back then!